Gov. Lamartine Griffin Hardman was

a progressive but stern governor. In 1929 he decreed no vehicles of the

University of Georgia should leave Clarke County. Under normal circumstances,

that’d be an easy rule to follow. But circumstances weren’t normal when

President Steadman V. Sanford was determined to unveil “the best football

stadium in Dixie” that fall. The Bulldogs were welcoming Yale to help christen

the new gridiron in the valley between the north and south campuses.

Circumstances

got more complicated when an Atlanta donor called with a gift of privet

Ligustrum—hedges to ring the stadium’s field. That’s when President Sanford hit

upon a scheme that might not invoke the governor’s ire. He involved the

governor’s son, Lamartine Griffin Hardman Jr., who was a UGA student. And since

the university’s fleet was limited, and the biggest truck belonged to the ROTC

department, Henri Leon (Sarge) Farmer was recruited to guide the stealth

mission to and from Fulton County.

When

young Hardman and his ROTC instructor struck out for Atlanta, they had

intentions of returning before dark. The truck’s headlights were on the blink. But

the journey took longer than expected. On the return to the Classic City, the

sun dropped. Sarge, ever prepared, pulled out a flashlight. He put his student

behind the wheel.

Clinging

to the running board, Sarge aimed the beam toward Athens. That worked—for a

while. Then it got darker. Army-like, he crawled onto the hood of the big olive-drab

truck. Hanging on with one hand and shining the light with the other,

Sarge—sprawled out—guided the governor’s son back into town and to the gate of

yet-to-be-dedicated Sanford Stadium.

Workers were waiting to spade the privet into the red clay. Legend suggests they, too, needed flashlights to beat the deadline before the Oct. 12, 1929, kickoff.

No

one knows whether Gov. Hardman ever yelped, but he was in the 50-yard line

seats—along with eight other Southern governors—to see the Bulldogs bite Yale,

15-0, between the hedges.

There

is more than one version of this story, but before the governor’s grandson, Lam

Hardman III, died, this is how he retold it. I’ve been carrying Lam’s story

around for 30 years. And then it hit me—the great-grandsons of Sarge Farmer and

L.G. Hardman Jr. live in Athens.

With

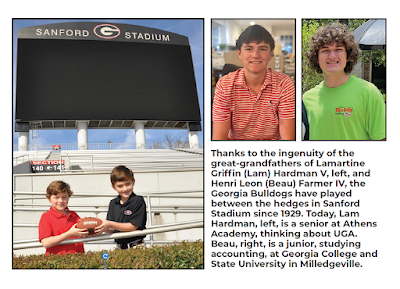

the help of their mothers, Catherine Hardman and Rebecca Farmer, Lamartine G.

(Lam) Hardman V, Henri Leon (Beau) Farmer IV and I took a trip to Sanford

Stadium to touch the hedges. That was in 2013. Lam was 7, and Beau was 9. For

50 minutes, between the hedges, I was younger than 10, too. The three of us

imagined the roar of 95,000.

As

I was looking at the privet Ligustrum, I flashed back to 1996. Vince Dooley was

on the phone. “The Olympics are coming,” he said. “If you want

some of the hedges, you best get on over here.”

Years

later, I bragged to Coach Dooley how well my hedges were doing. He trimmed my

pride, adding, “I don’t want to hurt your feelings, but you can’t kill privet

hedge.”

The

iconic football coach—turned green thumb—was right. Privet is an invasive-like

weed. Not only will it take over the farm; it will take over the imagination of

millions in the Bulldog Nation. Followers of the Red and Black believe there’s

something magic about playing “between the hedges.”

Just

ask Fran Tarkenton, Herschel Walker or Stetson Bennett IV.

You

can’t kill privet Ligustrum.

And

you can’t kill the legend of how the hedges got to Sanford Stadium.

Just ask Henri Leon Farmer IV or Lamartine Griffin Hardman V.