Monday through Friday, I watched him, in his burgundy, paisley-print robe and leather slippers. He stepped onto the sidewalk to fetch his newspaper. I remember an unlit cigar in the corner of his mouth. Reading the morning’s headlines, he climbed the steps of his white, two-story Victorian house at the intersection of West Orange and First streets.

As a sixth-grade schoolboy patrolman, I was intrigued. I wondered, “Who is he?” Those were the days when First Street was a narrow two-lane strip that morphed into the Waycross Highway on its way to Screven.

After I got to know this mystery man, the stately house was carved up and moved. The top half is now a single-story house on Hwy. 169. Progress made way for a new grocery store, Food Fair, which became Pantry Pride. Years later, the Dairy Queen occupies the corner where Joe and Leslie Thomas reared their two daughters, Esther and Elizabeth.

When I was in the 11th grade, Joe Thomas invited me to lunch. Other than seeing him, I really didn’t know the attorney. But I knew his partner at Thomas and Howard. Hubert Howard was one of my First Baptist Church Sunday school teachers.

When we shook hands at Smith’s Drug Store on Cherry Street, Joe insisted that I not call him “Mr. Thomas.” Earl Colvin, his UGA classmate, joined us. Both were lawyers, but Earl was a businessman. Among his enterprises was Colvin Oil Company, on the corner of West Orange and South West Broad streets, across from NeSmith-Harrison Funeral Home.

Earl Colvin, also a dapper dresser, didn’t know that I had been watching him, too. He also carried himself in a distinguished way. And one day, while I was sweeping the sidewalk in front of the funeral home, I saw the oilman walking my way.

Sticking out his hand, he said, “I’m Earl Colvin. Joe Thomas asked me to join the two of you for lunch.” Besides its pharmaceuticals, Smith’s was a popular meat-and-three café. Over a plate of pork chops, vegetables and a wedge of cornbread, they laid out a scenario that would make a decisive impact on my future.

When Joe finished his lunch, he waved off dessert and clamped down on a cigar stub. Earl pitched his and Joe’s alma mater, the University of Georgia. When I laid down my fork, Joe extracted his stogey and said, in his signature growl, “And when you get to Georgia, there ain’t but one #@&% club you need to join, Pi Kappa Phi.” Joe and Earl had been back-to-back presidents of the fraternity, circa 1930.

When I got to Athens in 1966, Joe’s advice stuck. Two years later, I followed in his and Earl’s footsteps as president of Pi Kappa Phi. That was a valuable experience in my leadership lessons over the past half-century-plus. I never imagined any of this in 1959, watching a courtly gentleman—in his silk robe—retrieve his Savannah Morning News.

In those days, there are two more things that I would have never imagined. Hubert Howard later promised that if I would go to law school, he would save me an office, between him and Joe Thomas. And when Joe Thomas died, in the early 1980s, I was asked to be a pallbearer at his funeral.

So why am I mentioning all of this?

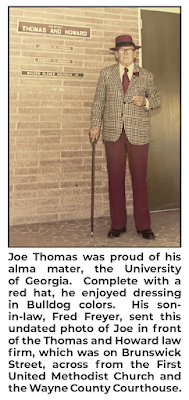

Joe’s son-in-law, Fred Freyer, who married Elizabeth (now deceased), called me from St. Simons. After we reminisced, Fred sent me a photo of Joe and his cigar—wearing UGA attire, including a Bulldog-red hat and matching trousers—in front of the law firm that guided me through dozens of transactions.

And that photo, in this upside-down world, helped me to dial up dozens of smile-worthy memories of Joe, Earl and Hubert.

Thanks, Fred.

dnesmith@cninewspapers.com